At the Foot of the Mountains

The Red Clay Creek has carved a gently rolling landscape out of the remains of ancient mountains.

This is a chapter in an occasional series about the history of Anson B. Nixon Park. I am publishing the chapters out of order (it worked for George Lucas). Since this one begins 300 million years ago I am guessing it will be chapter one.

Other Entries

Landfill to Park

Waterworks

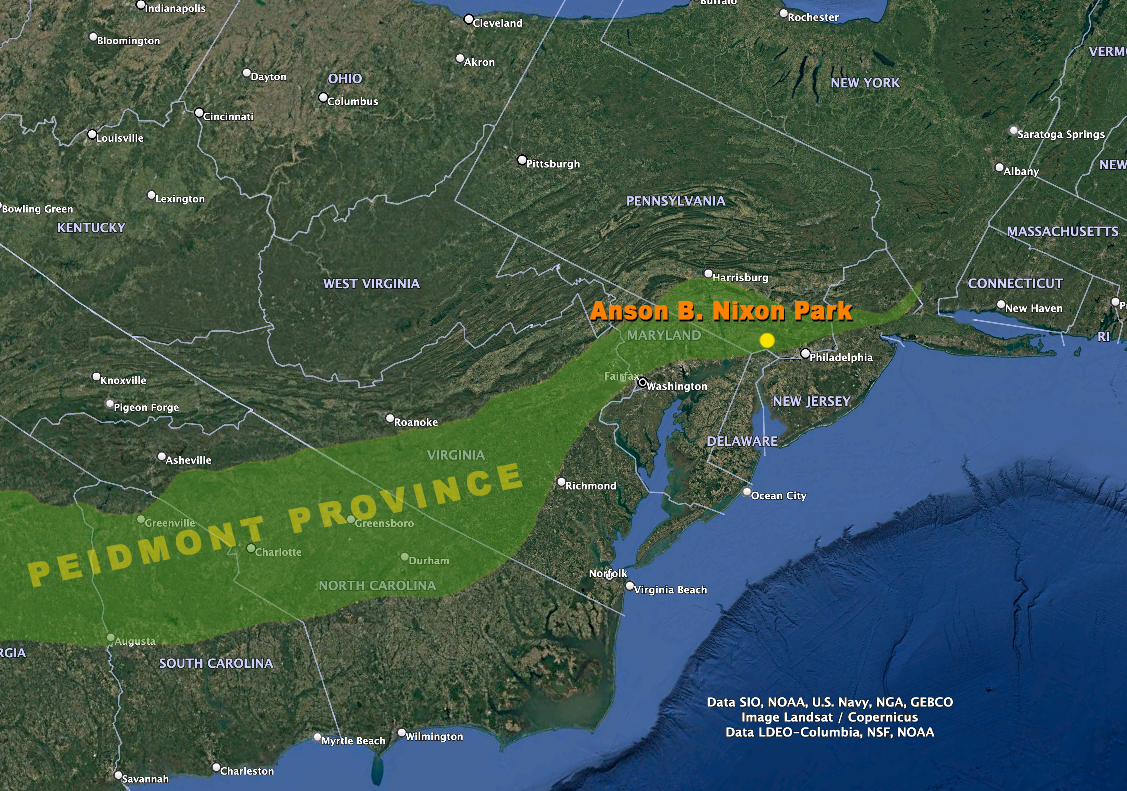

We live in the Piedmont (pied of the mont or foot of the mountains) with origins in a colossal event known as the Allegheny Orogeny.

Hundreds of millions of years ago the ancient continents that make up much of present-day North America and Africa collided causing the Earth's crust to buckle and fold forming a mountain range that likely rivaled the height of the modern Himalayas or the Alps where we live now.

For over 100 million years water carried away around 90 feet of mountaintop eastward every one million years.

The water slowed as it reached gentler terrain depositing sediment that eventually formed the gently rolling landscape of Chester county and its matrix of drainage systems.

Around ten thousand years ago, as the last ice age concluded, the climatic and ecological past began to be recorded in ancient pollen and plant remnants. Preserved within local bogs and lakebeds, these remnants offer a narrative of this history. Initial post-glacial warming favored the establishment of pine and oak forests populated by species like deer and black bear.

Then a multi-century period of warmer, drier conditions supported thriving eastern woodland fauna, including deer, turkey, beaver, and native elk (later extirpated from the region). Following this warmer interval, the climate moderated, leading to the development of the oak-hickory forests that were home to large predators like wolves and mountain lions.

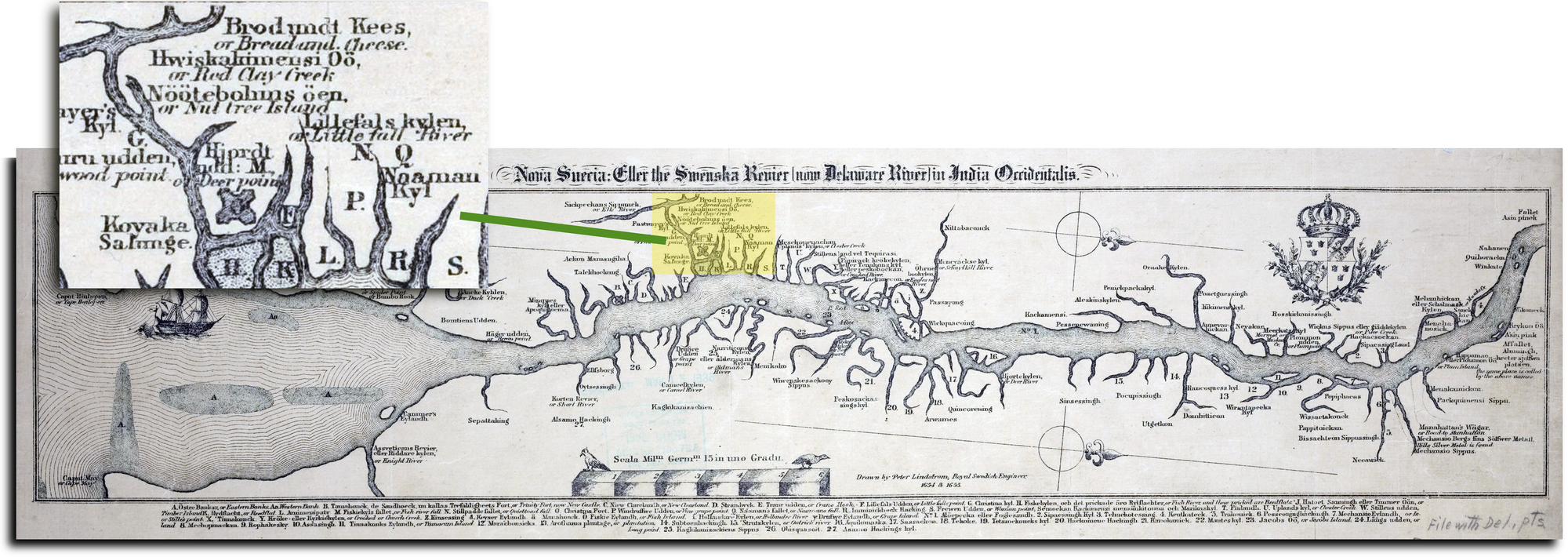

For many thousands of years the Red Clay creek was home to people who called themselves Lenape. They travelled downstream in the spring when spawning fish crowded the river banks and returned upriver to settle along the forested creeks for a winter of hunting.

A tree that was cut on the bank of the west pond at the park last March. The tooth marks and wood chips are the unmistakable work of a beaver.

Beaver dams also played a crucial role in shaping the waterways. Intensive fur trapping led to a near elimination of the beaver population, although it has since partially recovered.

During colonization farms and mills were established to capitalize on the rich land and power of flowing water. Between the late 1600s and the early 1900s, over 1,000 milldams were constructed in Lancaster, York, and Chester counties. The diverse, ancient pre-colonial forests were destroyed and fragmented as the land was cleared for agriculture.

This study reveals how mill dams significantly changed the creeks, which consequently reshaped the entire landscape. Evidence from stratigraphic analysis, radiocarbon dating, and historical records indicates that the valley floor of creeks like the Red Clay was once a broad, wooded wetland with a network of small, shallow, interconnected streams.

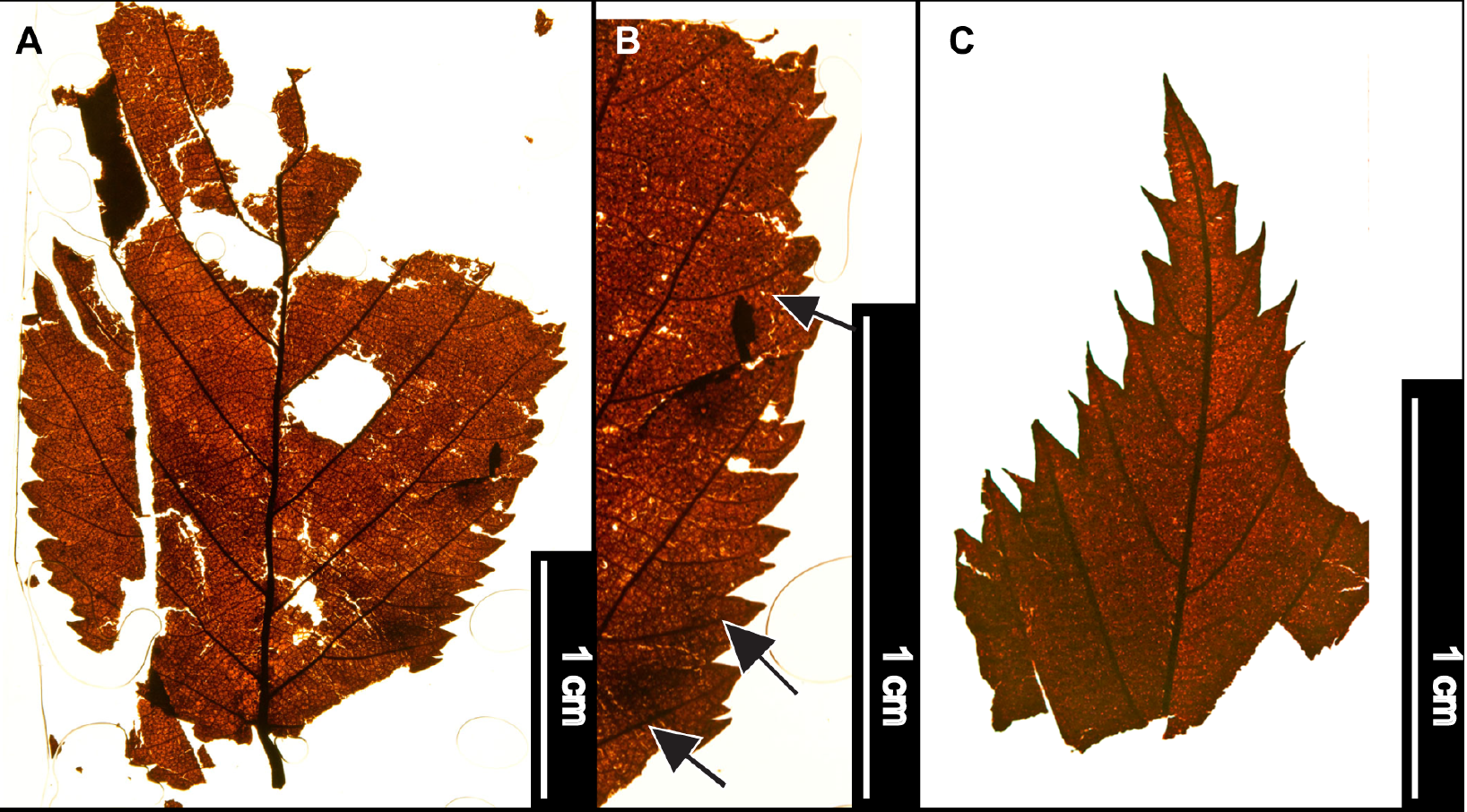

A recent study of sub-fossil leaves found in buried wetland soils along the White Clay Creek and similar nearby waterways provides a snapshot of the forest prior to significant European impact. The researchers found leaves from Hazel Alder, American Beech, Red and White Oak groups, Tulip Tree, Willow, Box Elder, Chestnut, and Hop hornbeam a mix of wetland and lower hill slope species.

Once we have some idea of our past we can appreciate how to shape the future.

Huge geological events like the Allegheny orogeny and smaller scale human actions like hunting beavers, building dams and clearing forests change the environment. No matter how hard we try we will not turn back the clock on these changes.

Our responsibility is understanding and preserving surviving natural processes and populations that create environmental stability.