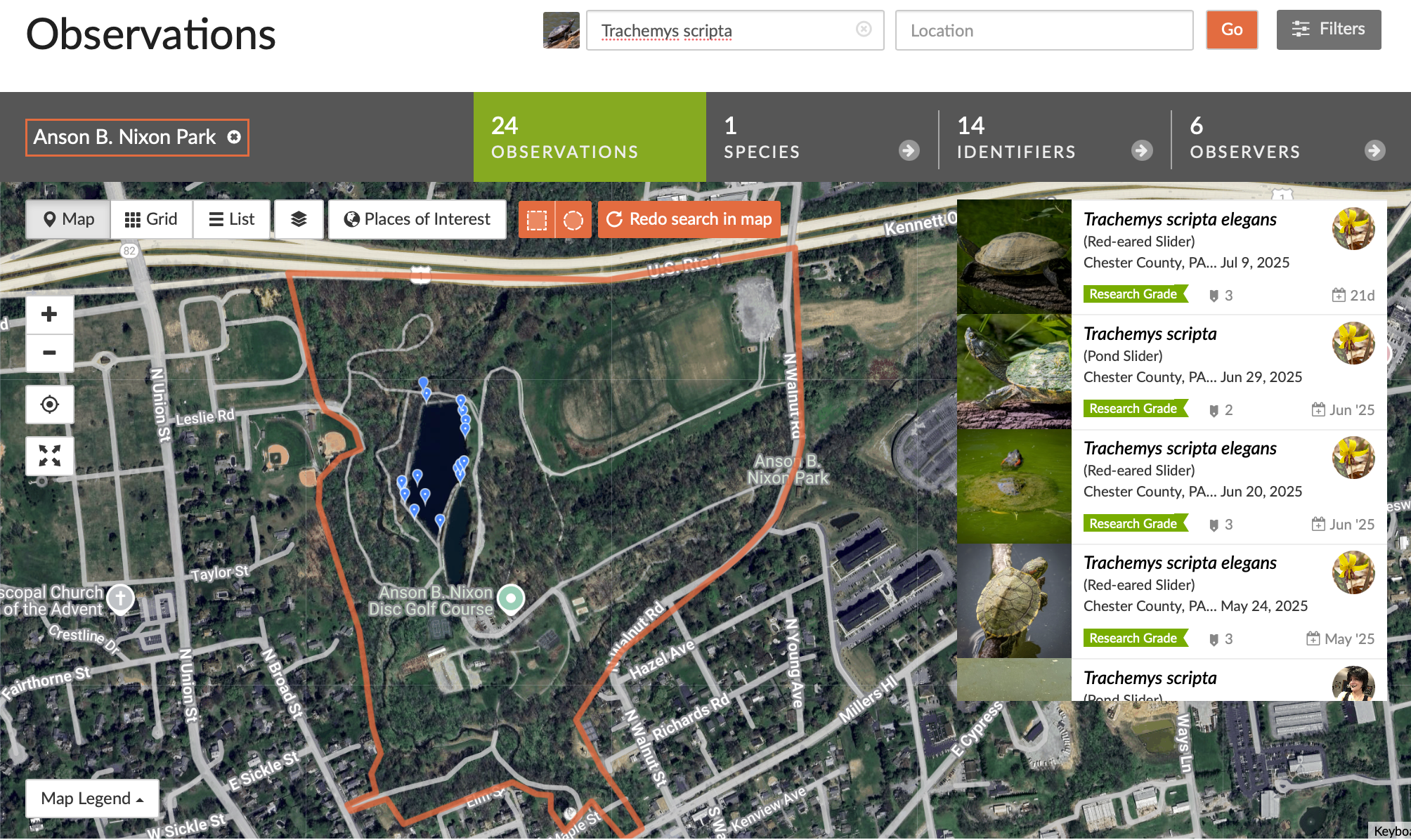

Pond & Red-Eared Sliders

This is the second species profile in the turtle series, here's the first entry that discusses things common to all the turtles at the park with links to the other profiles.

Pond sliders, Trachemys scripta, and subspecies the Red-eared slider, Trachemys scripta elegans are frequently seen basking on logs at the park. It's not unusual to see them crowding into every available inch of a good basking spot.

Red-eared sliders have a red stripe behind their eyes that pond slider's lack. Older red-eared sliders red stripe tends to become duller and blends in with other markings over time.

Both turtles have a moderately domed shell. Hatchlings are around a inch long, adult males top out a 5 to 8 inches, and females at 8-12 inches. They can live to be 30 or more years old. Males have much longer front claws than adult females who have longer hind claws for nest construction.

Pond and Red-eared Sliders, like most turtles, have a dense horizontal band of photoreceptor cells in their retinas adapted to viewing the horizon for predators. They are quick to flee when they sense movement, so approach basking turtles slowly. Try to make no sudden movements, and carry a pair of binoculars. If you are careful you can sort out exactly which kind of turtle you are looking at before they drop into the water. Older, larger, turtles tend to be less jumpy then the smaller ones.

Basking turtles extend their limbs and spreading their toes to present a greater surface to the sun. Warming is crucial to digestion, metabolism, and immune function. Exposure to ultraviolet rays is needed to synthesize vitamin D3 for calcium absorption and healthy shell and bone growth. Basking also helps turtles dry their skin and shell and inhibit the growth of algae and fungi.

In both species males reach sexual maturity at 2-5 years and females at 5-7 years. Breeding season is April to October. Both males and females mate with multiple partners.

Females leave the pond to find a sunny spot with soft soil. They may travel over a mile to find the perfect place. She digs a flask-shaped nest 4 to 5.5 inches deep with her hind legs and lays 6-11 (and as many as 30) small, leathery eggs roughly 1.2 to 1.7 inches long. She returns to the water, leaving the eggs to develop on their own.

The sun's warmth incubates the egg for the next two to three months. When they hatch, some tiny turtles dig their way out right away, others might stay in the nest through the winter, emerging in the spring.

Hatchlings are vulnerable to predators, It's estimated that only 1% of eggs survive to become a mature turtle.

Pond sliders are opportunistic omnivores with a diet that varies significantly between juvenile and adult stages. Young pond sliders are primarily carnivorous. Around 70% of their diet is made up of insects, snails, tadpoles, small fish, and the like to support rapid growth.

Older pond sliders develop the gut microflora necessary for efficient plant digestion and the carnivorous portion of their diet shrinks to 10% They eat aquatic plants and those at the pond's edge. Both young and old turtles forage in the early morning or late afternoon.

Red-eared sliders are not native to Pennsylvania. These natives of the Gulf coast states and Mississippi river were popular pets, that have become an invasive species when released into the wild (it is illegal to release red-eared sliders into Commonwealth waters).

Red-eared sliders alter aquatic environments by consuming local plants and small animals. They also compete with Pennsylvania's indigenous turtle species for sunny basking spots, and nesting locations. Native populations are susceptible to disease red-eared sliders may introduce.

A 1975 federal law banned the sale and distribution of turtles with a carapace (shell) length of less than 4 inches as pets.

Pennsylvania requires a permit for a person to possess, purchase, or receive a non-indigenous or exotic reptile, and a dealer Permit is required for commercial dealing in these species.