The Yellow Trout Lily

This is a longer post than usual, but I have been enjoying learning more about trout lilies, the closer you look the more you see.

Having suffered minimal disturbance for possibly three hundred years the beech grove at Anson B. Nixon park could be one of the few local remnants of a much more vast pre colonial forest. The survival of the beech grove is so unlikely as to be miraculous. It's home to a phenomenal colony of yellow trout lilies that is likely centuries old.

If you haven't been to look at them this spring you are missing out.

The Yellow Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum), is native to the woodlands of eastern North America. Sometimes it's called Fawn Lily, Yellow Adder's-tongue, or Yellow Dogtooth Violet.

Trout lily leaves are easy to spot. The leaves are waxy, oval or lance-shaped, 3 to 9 inches long, smooth edged, grayish-green with dark bronze brown spots like the pattern seen on brook trout, thus the common name.

They have a single flower on a stem growing over the leaves. The flower points downwards and has six yellow petal-like parts called tepals that bend backwards. These tepals are bright yellow inside and purplish, brownish or bronzy on the outside. There are six stamens with brownish, reddish or rusty-red anthers.

The flowers close at night or in overcast conditions, an evolutionary phenomenon called "nyctinasty". Darwin proposed this reduces the risk of freezing, while another theory suggests that it conserves energy and scent for daytime pollinators. Nytinasty also keeps pollen dry and powdery, making it easier for insects to transfer.

Trout lilies are spring ephemerals, plants that grow rapidly before the forest canopy shades the ground. They emerge when the forest floor thaws and daylight hours lengthen. Before long flowers bloom attracting pollinators emerging from their winter dormancy.

These early blooming species are especially important to early-season bees. The Trout Lily Mining Bee (Andrena erythronii) is a solitary bee associated with trout lilies, although it will collect pollen from other flowers.

Solitary bees make up an amazing 98% of all native bee species in North America. Most of their one-year lifespan occurs underground as larva and pupa. When they finally emerge as adults, they only live for a few weeks. The males' only job during that time is to mate, while the females are busy building nests and laying eggs. Nests can be built underground, in plant hollows, rock crevices, or even out of a special plastic-like material that the bees make. Some bees will even take over the nests of other species.

Trout lilies reproduce sexually from seeds and asexually by vegetative propagation from an underground corm; an oval, bulb-like structure measuring roughly ½ to 1 inch long.

Seed capsule, ant with seed showing the gelatinous elaiosome.

Once pollinated trout lilies rapidly develop seeds in an oval capsule, about ½ inch long. The seeds have elaiosomes, a fleshy, calorie and nutrient dense structure. Worker ants carry the seeds to their colony, eat the elaiosome and discard the seed that then germinates. This win-win relationship with ants is called "myrmecochory" (meaning "the ant's circular dance").

Trout Lilies have a corm that stores starch produced during this year's growing season to fuel rapid growth next early spring. The corms are often 4-12 inches below ground, a depth that keeps the corm is kept moist, protected from freezing during the winter, and makes it less likely to be eaten by animals. Trout Lily corms produce runners that form new corms and genetically identical plants. One common name "Dogtooth Violet" comes from the corm's shape resembling a dog's canine tooth.

A single trout lily can form a colony that may last for centuries. These colonies have many more non-flowering plants than flowering ones. Less than 1% of the colony's plants flower each year. Trout Lilies only flower after they reach a certain size and have stored enough energy. This takes 4-7 years or more, so most plants in a colony are too young to flower and only have one leaf.

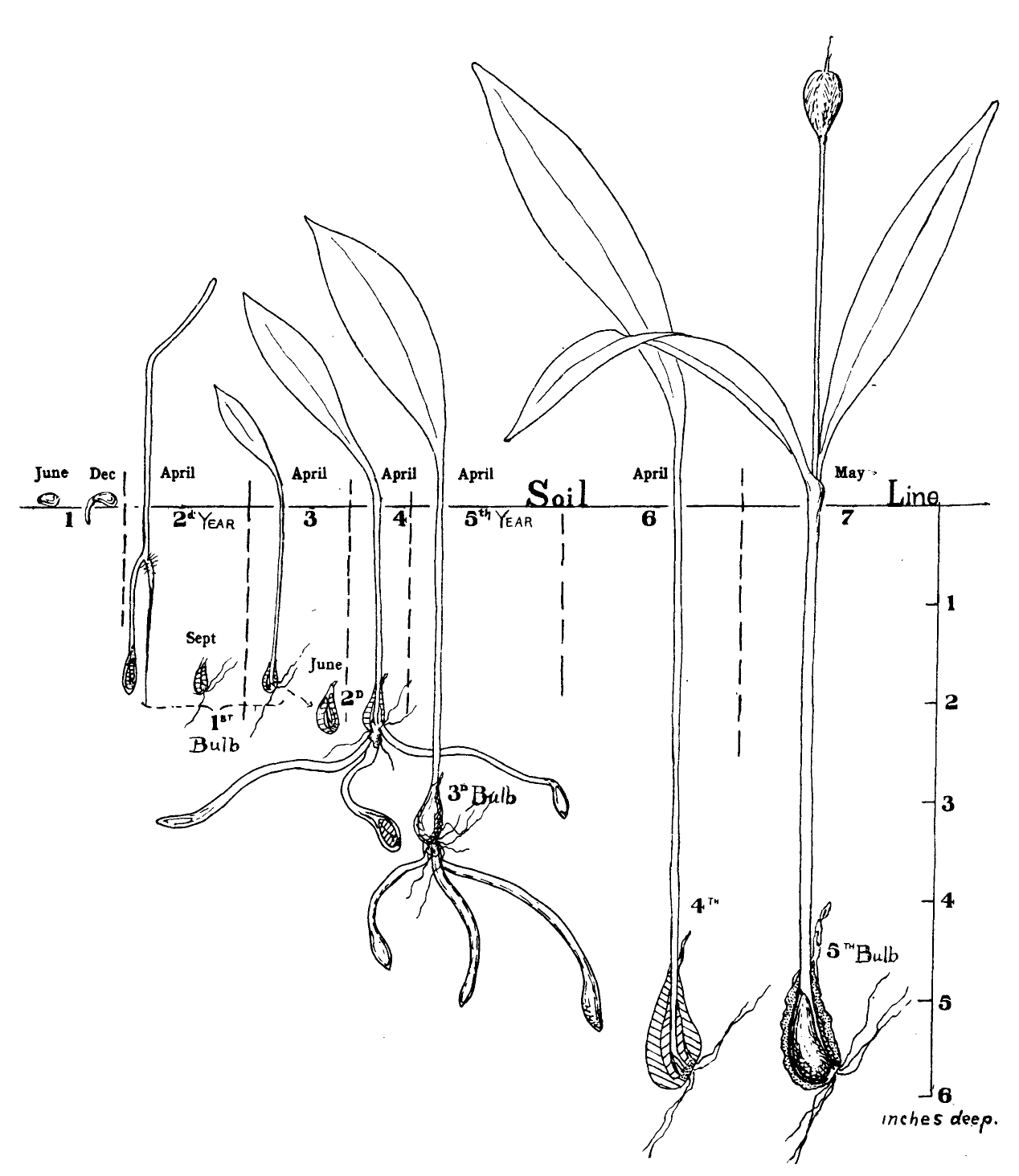

Trout Lily Growth Stages

| Year 1 (June-December): Seed stage. |

| Year 2 (April): The seed sprouts, a single embryonic leaf (the cotyledon) grows down into the soil first, then the tip pops up above ground. At the bottom, underground, the very first tiny bulb starts to form. Notice it's not very deep. |

| Year 3: The first bulb sends up a single, slightly larger leaf. Underground, a new, slightly deeper bulb (marked 2nd) is forming to replace the first one. |

| Year 4 (April): A single leaf appears. The second bulb is getting deeper. The roots shown here help anchor it. The plant might stay like this for several years, just making a new bulb in place without getting much deeper. At this stage runners help form new bulbs going deeper spreading the plant out. |

| Year 5 (April): Still likely a single leaf, the third bulb continues its journey downwards. |

| Year 6 (April): The plant is finally mature to send up two leaves instead of one, and the 4th bulb has reached its final, deepest level, usually several inches underground. |

| Year 7 (May) & Onwards: The mature plant produces a flower along with its two leaves. From now on, it will likely flower each year, forming its replacement bulb at roughly this same depth. |

Illustration from: The Origin and Development of Bulbs in the Genus Erythronium Frederick H. Blodgett Botanical Gazette 1910 50:5, 340-373

Trout lily colonies prioritize survival over diversity. They spread slowly and steadily, taking over stable areas of the forest floor. This strategy makes them locally successful, but since they mostly reproduce by cloning, the plants in one colony are very similar genetically. This lack of genetic diversity could be a problem because it might make them more vulnerable to new pests, diseases, invasives, or environmental changes.

To ensure the survival of this delicate and beautiful colony, we must prioritize minimizing our impact by staying on designated trails and refraining from picking flowers or digging up plants. Safeguarding our trout lily colony and its fragile woodland habitat is vital for preserving the region's biodiversity and natural heritage for the enjoyment and appreciation of future generations.

Thanks to Carol whose comments on this post piqued my curiosity to further explore trout lilies